“Richard, what does it mean for a Cub Scout to be prepared?” My Den Mother waited for my answer. I tugged on my scout shirt collar. The night before I had studied the Cub Scout manual. I hoped to advance from Tiger to Wolf Scout. My seven-year old mind wondered, “What does Mrs. Chapman want? What’s the right answer?” Later in life I faced similar questions under different circumstances when Dad described how he wanted to die. His distant death seemed like a remote possibility as we talked. Dad had lived in his home of 50 years in suburban Milwaukee. His active lifestyle that included slogging through trout steams of central Wisconsin close to midnight wasn’t congruent with our discussion of death on that warm spring morning.

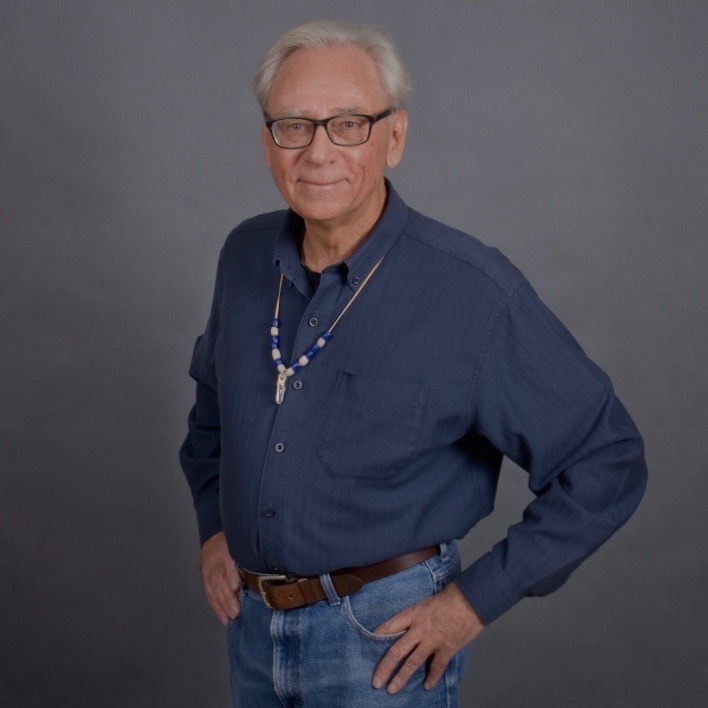

“I’ll be around for a long time,” Dad said. “I don’t want you to worry. But, we should discuss how I want to die. I don’t want to hang around with an extended illness. I don’t want to suffer or to be a burden for you kids. When the time is right, I just want to die.” My belly churned as Dad spoke the unmentionable word. We didn’t talk about death in our family. Mother admonished us to speak of nice things instead. My sister and I called him “Dad” most of our lives. At some point, as he aged, we began to refer to him by his initials: “WFW.” I’m not sure why we made the change. Perhaps it was easier for us to prepare for Dad’s ultimate demise when we referred to him as WFW instead of Dad? Maybe we spoke of nice things when we discussed WFW’s eventual death instead of Dad’s death? “Pneumonia is a comfortable death,” the emergency room physician reported. “Most of his systems have shut down. He has an embolism in his gut and failed kidneys. We could give him penicillin to cure his pneumonia. He’ll return to the nursing home until something else brings him back here. It’s really about his quality of life. We can keep him alive, but what does he want?” “Want?” I wondered. “What does WFW want?” I turned from the doctor and recalled my long ago conversation with Dad. Dad knew exactly what he wanted when he said, “It asks on this healthcare power of attorney form if I want chest compression for heart failure. I have a pacemaker. I can’t have chest compression. Chest compression would break my pacemaker. The pacemaker is expensive, so just let me die.” I recall my loss of words as I spoke with Dad. I pondered how to ask Dad about the value of a pacemaker compared to his life. Unable to think beyond nice things, I never asked the right questions to get the right answers. Instead, I said, “Dad, check the box for no chest compression.” My reply seemed like a simple decision. I assumed Dad would suffer a heart attack and I would know exactly what to do. Our pacemaker conversation felt like a scene in a play, something I watched, but hadn’t happened to me. I never asked Dad what he wanted if he was stricken with an embolism, kidney failure, and pneumonia. I turned to the physician, “I need time to think and telephone my sister.” “I’ll wait for your answer,” he replied. In my call with my sister we remembered that Dad wanted a comfortable death. We knew he didn’t want to suffer. I returned to Dad’s bedside. He was chewing a corner of his blanket. Certainty of his death enveloped me. “I’m so cold,” he murmured. I tucked Dad’s blanket around his shoulders. “Good bye, Dad. I’ll miss you. I love you,” I said close in to him. I left Dad’s room, prepared to answer the doctor’s question. If this essay is meaningful, please like or tweet below or leave a comment. Thank you for your interest and possible action you may take. Richard Wilberg, MS, PLCC, ACC Life Coach for Personal Fulfillment and Career Success

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About the AuthorI write personal essays, creative non-fiction, flash fiction, and self-development articles from my home in Madison, Wisconsin.

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed